Understanding Visitations: Why This Ritual Still Matters Today

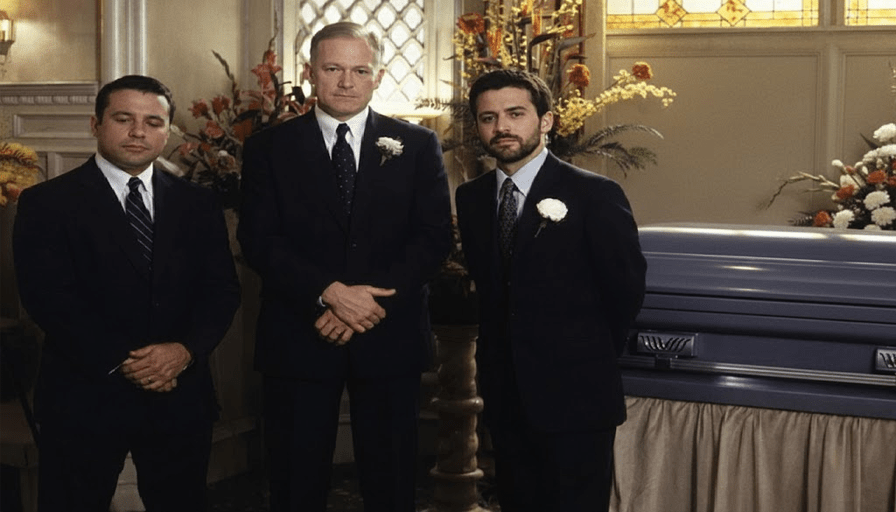

When someone dies, families enter a strange in-between world. Everything moves quickly while, at the same time, nothing makes sense. People begin making decisions instinctively, sometimes based on tradition, sometimes because someone needs to take the next step. In those first days, a quiet ritual often forms before anyone even names it. Photographs are gathered, playlists are chosen, relatives knock on the door with food or flowers. And in the middle of all that motion, one moment often becomes the emotional center of early grief, the visitation.

A visitation is much more than a time slot on a funeral schedule. It is a space where reality begins to settle. Anthropologists describe these moments as liminal, a threshold between what life was and what it is becoming. Families often describe the visitation as the first moment they truly see the loss reflected in the eyes of others. A woman once told me, “When people started arriving, it was the first time I felt supported instead of overwhelmed.” That simple sentence captures what a visitation does. It absorbs the first shock. For families who want to understand how a visitation compares to other types of gatherings, such as a memorial service or a celebration of life, we explain the differences in more detail in our guide: Choosing Between a Memorial Service and a Celebration of Life: What’s the Real Difference?

The idea of coming together before a funeral is not new. Early Christian households gathered around the family almost immediately, bringing prayer and food to soften the weight of those first hours. These practices eventually shaped many of the rituals found in Catholic funeral customs, which you can read more about in our detailed guide: Catholic Funeral Traditions: A Guide to Customs, Rites and Symbolism. Jewish mourning traditions emphasize the same point, grief is not carried alone. In Victorian America and Britain, the deceased was placed in the family parlor so neighbors and friends could come by to offer condolences. Irish wakes blended tears with stories, music, and an honesty about emotion that feels surprisingly modern. African American viewings, shaped by history and cultural resilience, focus deeply on dignity and the presence of community at a time when it matters most. Today’s visitation grows directly out of these practices.

Although the term “visitation” is most common in the United States and Canada, similar rituals exist everywhere, each shaped by cultural expectation. In many parts of the U.S., especially the Midwest and South, an open casket is the norm. In the United Kingdom, families often prefer a smaller and more private visiting hour. Scandinavian families lean toward simplicity and quiet reflection. In Southern Europe, velatorios often begin only hours after a death, and the room fills quickly with relatives and neighbors who believe strongly in being present immediately. The customs differ, but the emotional logic underneath them is the same. People gather because loss is not meant to be faced alone.

The emotional structure of a visitation is more complex than it appears. It helps soften the shock by providing a shared space where the loss becomes real in a gradual way. Guests walk in quietly, pause, and then approach the family with a hug or a gentle hand on the arm. These small gestures communicate something that words rarely capture, “I see your pain, and I am here.” Families often tell me that the most healing part of a visitation is hearing stories they themselves never knew. A coworker describes a surprising act of kindness. A childhood friend recalls something funny or meaningful. A neighbor remembers a small moment that captured the person’s personality. Through these stories, the identity of the person begins to reform, not as a memory frozen in time but as something living inside the people who knew them.

Whether the casket is open or closed is a personal and sometimes cultural decision. Some families welcome an open casket because seeing the person at peace helps them begin to accept the loss. Others prefer a closed casket because privacy feels more respectful, or because cremation has already taken place. Families often say, “We want people to remember her as she was,” or “Seeing him helps us let go.” There is no universal right answer. The right decision is the one that aligns with the emotional truth of the family.

Modern visitations have also adapted to the way people live today. Families are often spread across different countries. Travel is expensive and sometimes impossible. As a result, hybrid and virtual visitations have become part of contemporary mourning. Someone may sit in the funeral home while a relative joins from another continent, signing a digital guest book or sending a recorded memory. Even in virtual form, the purpose remains the same. People gather to acknowledge a life and support those who feel the loss most deeply.

Creating a meaningful visitation begins with understanding who the person was. A table filled with personal objects, whether it is a fishing rod, a camera, a favorite book, a military medal, or a pair of worn hiking boots, can say more than a formal tribute ever could. Families often feel comfort when they see visitors pause at these items, smile softly, and whisper to each other about the person they remember. The room becomes not only a place of mourning but a space that reflects a life lived with meaning.

The atmosphere around the visitation matters just as much. Music, lighting, flowers, photographs, and the quiet movement of people through the room create an environment that shapes how guests feel and how they connect. Some families prefer steady conversation and shared laughter. Others create a gentle, introspective space. The emotional tone of the visitation does not need to follow tradition. It needs to follow the truth of the person being remembered.

What makes visitations essential, even in a digital age, is the act of showing up. A visitation makes grief visible. It reminds families that the person they lost mattered to many people. It gives the community a chance to carry part of the emotional weight. It also helps families transition from the raw shock of early loss into the more structured farewell of the funeral. The gathering becomes a bridge, a moment where love, memory, sadness, and connection all exist in the same room.

In the end, a visitation is not simply a custom. It is a profoundly human response to death. It acknowledges that remembering is not something we do in silence. We need witnesses. We need stories. We need the presence of others to help us understand what has been lost and what remains. A visitation gives families a moment to breathe, to be held, and to begin the difficult work of grieving together. Above all, it affirms that a life had meaning, and that meaning lives on in the people who gather to remember.

If you have any questions, comments, or feel certain information is missing after reading this post, feel free to contact us via the contact form.